WELCOME TO CLARK COUNTY

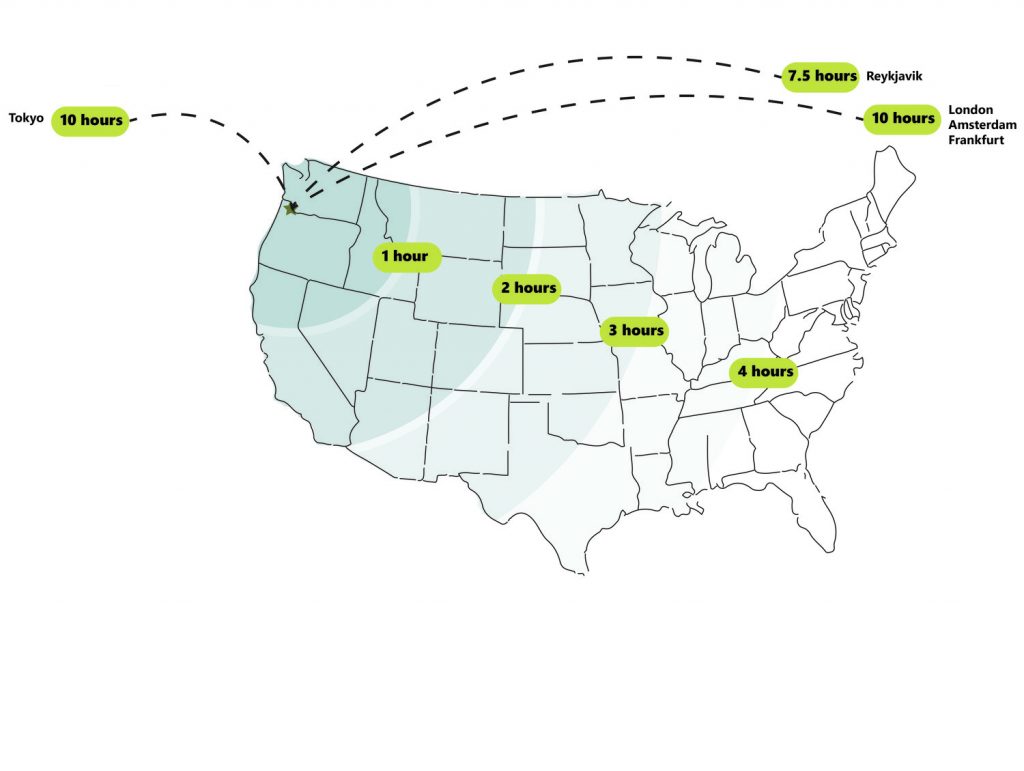

Situated in the heart of the Pacific Northwest, Clark County serves as the premier Pacific Rim gateway to the U.S. and Canada.

It is exceptionally well-positioned to access major West Coast, Midwest & international markets through multimodal connections to I-5 and I-84, deep-water ports, rail, and the Portland International Airport (PDX), voted the nation’s Best Airport for years.